The year 2025 marks four decades since the brilliantly bizarre, genre-defying movie Brazil was released to audiences. Written and directed by Monty Python’s Flying Circus alum Terry Gilliam, Brazil does not, as one might think, take place in South America’s largest country, but in a techno-dystopian, quasi-futuristic (or perhaps parallel-universe) version of England.

The movie takes its name from the jaunty 1939 samba “Aquarela do Brasil” (later popularized in the USA as “Brazil!”). The song’s cheerful melody serves as an ironic leitmotif for protagonist Robert Lowry (played by Jonathan Pryce), a hapless everyman living a life of quiet desperation he often dreams of escaping.

Lowry – a weak, lonely man, employed as a low-level bureaucrat by a nameless and tyrannical government – is the most unlikely of heroes. He knows he is nothing more than a cog in a very large and horrible machine, but is too passive to strive for anything better. Aside from grandiose flights of fancy in which he rescues a mysterious woman from giant robots, he seems to have abandoned all hope of a better tomorrow.

As imagined by Gilliam, Lowry’s world is a nightmare technocracy, in which the government is corrupt, oppressive, and incompetent. Regular people are subjected to constant surveillance, arbitrary restrictions, and onerous paperwork at every turn, while members of the upper class enjoy lives of ease and luxury. In this society, the secret police don’t just brutalize you, they charge you for the cost of doing so. Indeed, the miserable task of hand-delivering a refund check to the wife of a wrongly-arrested man who was tortured to death is the event that propels Lowry out of his routine and into the plot of the movie.

Are We Living in Brazil?

Brazil is, nominally, a comedy. The exaggerated sets and costumes, expressionist cinematography, and absurdist dialogue are clearly intended to be (and often succeed at being) humorous. But, as with other great films, like Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, and Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, Terry Gilliam’s Brazil uses humor to tackle serious issues.

Many parallels exist between the exaggerated horrors of Gilliam’s cinematic fever-dream and our world today. Pervasive surveillance, mindless consumerism, Kafkaesque bureaucracy, rampant abuse of power, predatory dominance of the masses by a wealthy, well-connected elite, deteriorating social fabric, over-reliance on flawed technology, and other systemic issues are all presented in satirical form. But what really sets Brazil apart from other dystopian films is that it focuses not on the dominant system itself, but on the psychological impact of the system on the individual.

Unlike more well-known stories like 1984 and Brave New World, much of Brazil takes place within the mind of one, insignificant person. Sam Lowry is a tiny man whose existence makes no impact. But we see his dreams, and we feel his loneliness, his yearning for freedom, and his hopelessness. Through the sensitive, understated performance of Jonathan Pryce, we see how a man’s will can be broken so completely that he resigns himself to a life devoid of anything lifelike.

More than anything else, it is the sense of isolation and apathy that makes Brazil more relevant than ever. Since the movie was released in 1985, depression has skyrocketed and sperm counts have plummeted. We are more addicted to technology, and less connected to each other. Today, we are all Sam Lowry.

The Lesson of Brazil

It is tempting to see Brazil as a dismal prophecy that has already come true. But to do so would be to ignore its final and most important warning: the most important battle is the one inside our minds.

Technology, consumerism, corruption – those things are here, and, like the giant robots that represent them in Lowry’s fantasies, there is no way to stop them. But to surrender hope, to reject truth, to relinquish freedom, and to give up on love – that is a path we need not take.

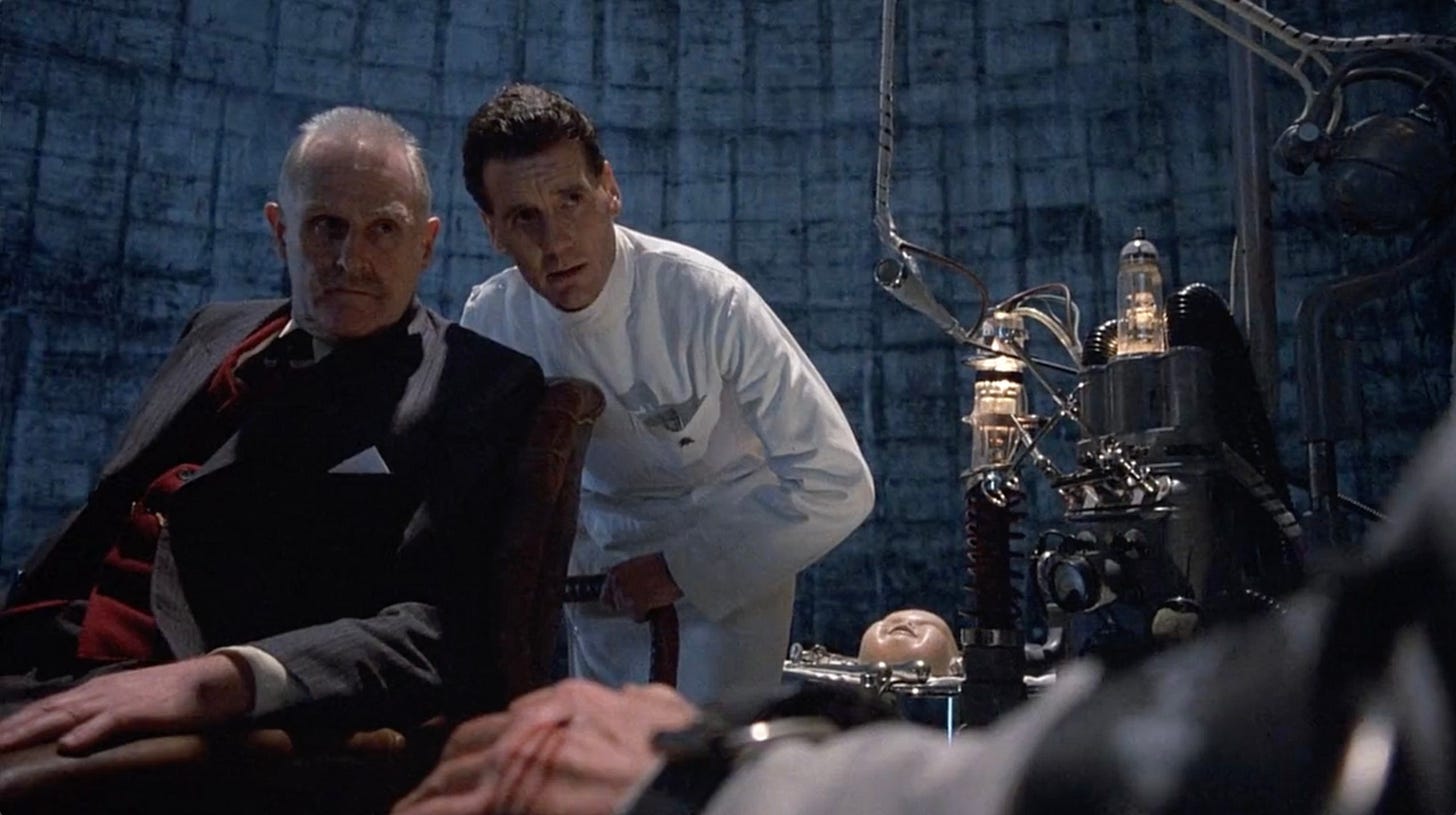

At the end of Brazil, Sam Lowry discovers that the key to freedom and happiness exists within his own mind. Strapped to a torture chair in the euphemistically-named Ministry of Information Retrieval, he lets go of the reality around him and slips irrevocably into the more rich and desirable world of his own fantasies.

Like everything else in Brazil, Lowry’s “escape” is exaggerated for impact. Gilliam is not actually suggesting that insanity is the way to escape tyrannical forces, but rather that we have the power to keep even the most tyrannical forces from conquering our minds. What happens to our bodies may be outside our control, but as Lowry dramatically demonstrates, what happens to our minds and our souls is up to us.

For Sam Lowry, it was already too late. He and the world of Brazil had gone too far to turn back. For us, it is not yet too late. We can put down our glowing screens, silence the maddening “notifications” that interrupt every meaningful moment, and actively seek out opportunities for kindness, togetherness, and humanity.

If Brazil teaches us anything, it is that freedom is not a state of government, it is a state of mind. Despite the uncomfortable resemblance between Terry Gilliam’s 40-year-old nightmare and our present-day reality, we are still free to choose hope, truth, freedom, and love.

I saw "Brazil" in high school. It was impactful for me—it pushed the dystopia button in my head pretty hard!

excellent. i saw it on first release and didn’t get it. time for a rewatch.