Post-Soviet States Prove Limited Government is Best

Would you rather live in Estonia or Moldova?

What kind of government will most effectively foster a nation’s stability, prosperity, and well-being? For millennia, political philosophers have been divided into two camps: those associated with libertarianism and capitalism who believe that government is, at most, a necessary evil that should be minimized to allow each individual to fulfill his or her potential; and those associated with authoritarianism and socialism who believe that government must have broad authority to act on behalf of society to ensure the common good.

Historically, these arguments have been largely theoretical, because there was no way to know what would have happened if a nation had chosen different policies. Moreover, most countries implement a mix of policies from both ideologies – some, such as Switzerland and Denmark, very effectively, and others, such as Somalia and Venezuela, very ineffectively. This has made it difficult to study the effects of governance while controlling for variables such as culture, size, population, and geography.

Fortunately, recent history has provided the opportunity for a head-to-head comparison. After the disintegration of the USSR in 1989, the post-Soviet states had carte blanche opportunities to create whatever governments they chose. This provides us with a close-to-perfect, real-world case study in political science.

Consider Estonia and Moldova. Both nations are comparable in terms of population, ethnicity, religion, size, geography, and history, but took contrasting paths following independence. Estonia chose a libertarian approach, focusing on free markets and individual freedom. Moldova continued in the Soviet tradition, establishing a command economy with authoritarian policies.

The Philosophy of Freedom

The opinion that higher levels of governance are negatively correlated with quality of life is almost as old as government itself. In the Biblical book of Samuel, written over 2,500 years ago, the prophet Samuel warns the Israelites that establishing a monarchy would inevitably result in oppression and misery, predicting that, “He will take a tenth of your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves. When that day comes, you will cry out for relief from the king you have chosen” (1 Sam. 8:17-18).

Six centuries later, the Roman historian Tacitus complained, “I have to present in succession the merciless biddings of a tyrant, incessant prosecutions … the ruin of innocence, the same causes issuing in the same results, and I am everywhere confronted by a wearisome monotony in my subject matter.” The theme of these early works is clear: governments predictably descend into tyranny, inevitably causing misery for their subjects.

More recently, the 18th century saw the emergence of Enlightenment philosophers, such as Voltaire and David Hume, who proposed that government should be restricted in size and scope in order to permit people as much freedom as possible.

During the same era, the political ideology of classic liberalism rose to prominence. Thinkers such as John Locke, Edmund Burke, and John Stuart Mill argued passionately in favor of individual liberty and limited government, as did many of America’s Founding Fathers, particularly Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine, who advocated minimizing government in order to maximize human achievement and happiness.

The theory that limited governance promotes economic as well as personal development rose to prominence following the publication by Adam Smith of his seminal work An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. This work became the genesis of the Austrian School of laissez-faire economics founded by Ludwig von Mises, which in turn inspired Nobel Prize winning economist Milton Friedman, as well as more radical anarcho-capitalists such as Murray Rothbard, who advocated for the abolition of taxation and the privatization of public services.

The Philosophy of Authoritarianism

The opposing perspective – that strong governance is vital for human and economic development – also dates to ancient times. In the fourth century BCE, Plato argued that autocratic rule by an enlightened philosopher-king was the most effective form of government, warning that unrestrained individual freedom leads to chaos and disorder.

Anticipating the social justice movement by over two millennia, Plato suggested that the aim of government should be to foster the virtues necessary for a healthy and productive society, and that this should be done through the establishment of laws and regulations.

In the modern era, the concept that government intervention is desirable in social and economic affairs – a philosophy broadly characterized as left-wing ideology – traces its DNA to the writings of 18th century intellectual Jean-Jacques Rousseau. His ideas were instrumental in inspiring the French Revolution and the subsequent development of socialism in France and throughout Europe. His advocacy of a civil society based on the general will of the people, of social equality, and of a strong government remain at the core of socialist philosophy today.

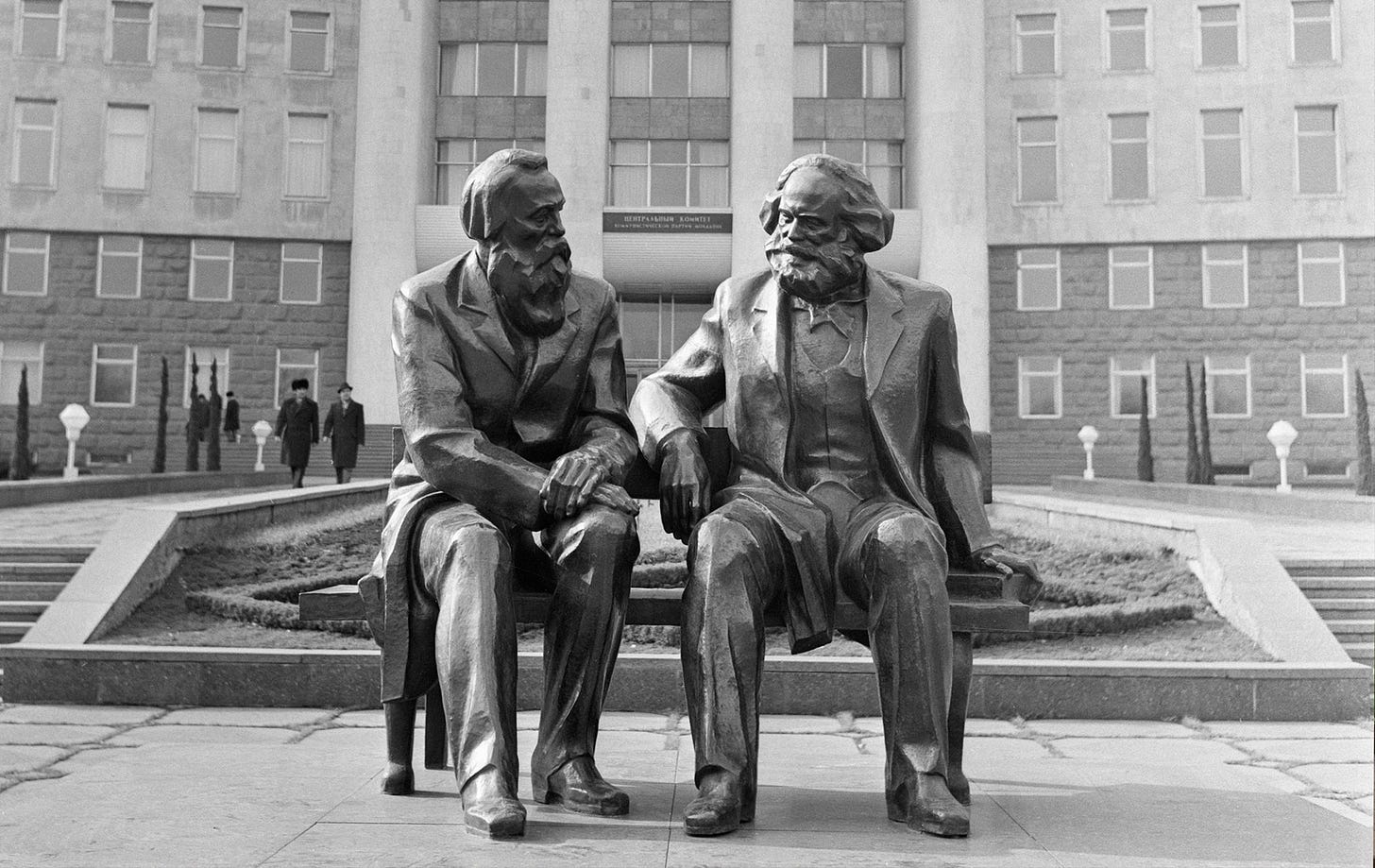

Rousseau’s ideas were taken to their logical conclusion by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the Communist Manifesto. In this work, Marx and Engels argued that a planned economy would be more efficient than a market-based economy, and that government control of both property and the productive capacity of a nation (“the means of production”) would facilitate an equitable, classless society. They proposed that income should not be based on a person’s skills or ability, but rather on what was required to provide for basic needs. In this socialist utopia, the state ensured that every citizen contributed what they could, and received what they needed (“from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”).

The ideas proposed by Rousseau, Marx, and Engels have been, and continue to be, highly influential in academic and political circles. Preeminent economist John Maynard Keynes followed in this tradition when he suggested that governments should intervene in the economy to stimulate aggregate demand, as well as to manage inflation, unemployment, and other macroeconomic factors. He argued that fiscal policy tools such as taxation and spending could be used to manage the economy, and that monetary policy tools such as interest rates and money supply could effectively manage inflation.

Keynes’s advocacy for high levels of government intervention were integrated into the economic policies of many nations, including the United States and the United Kingdom and are currently woven into the fabric of development initiatives proposed by prominent thinkers such as Thomas Picketty, and non-governmental organizations such as the United Nations and World Economic Forum.

According to these proposals, widespread individual autonomy and free enterprise have led to unacceptable levels of income inequality, have been catastrophic for the environment, and are incompatible with emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and genetic engineering. They argue that individualism undermines societal progress that requires collective action, and that traditional capitalism focuses on short-term gains without considering long-term costs or negative impacts on the environment and global climate. They believe a more equitable and sustainable system is needed to ensure that the benefits of economic growth are shared by all segments of society, and that central management by national and international governing bodies is necessary to achieve this goal.

The Eastern Bloc Experiment

As representatives of these contrasting ideological traditions, Estonia and Moldova are exemplary. Estonia’s leaders heeded the advice of Adam Smith and the Austrian School, while Moldova hewed to the tradition of Marx and Keynes.

Psychologically, the legacy of Soviet rule seemingly influenced Moldova to continue with a tradition of strong government intervention, while it motivated Estonia to move as far as possible in the opposite direction.

The consequences of these choices have been overwhelmingly in Estonia’s favor.

Qualitiative Evidence

The Estonian parliament has robust turnover in membership, while Moldova’s parliament is largely composed of entrenched elites.

Estonia has a high level of citizen awareness and participation in democratic institutions, while Moldovans view voting as meaningless because of the influence wielded by oligarchs.

Within a few years of independence, Estonia had a strong and well-developed government with a transparent and accountable system of democratic rule. After twenty years, the country’s competitive market economy, low levels of corruption, and well-developed social safety net have facilitated robust economic growth, high levels of foreign investment, and a Western European-level quality of life.

In Moldova, the government is both ineffective and despotic, and inadequately restrained by rule of law. A lack of transparency and accountability has resulted in low levels of economic growth, limited foreign investment, and quality of life comparable to that of developing countries. Organized crime, poverty, and unemployment remain stubbornly high, and many citizens are nostalgic for the days of the USSR.

Research by Williamson and Mathers found that economic and cultural freedom (indicators of limited government intervention) are directly correlated to GDP growth. According to their analysis, Estonia’s growth rate of 1.81 was the result of its high levels of economic and cultural freedom, while Moldova’s disappointing growth rate of -1.23 was the consequence of its substantially poorer performance in these key variables.

Quantitative Evidence

Estonia has a score of 76 on the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), which is 12th in the world. This indicates a high degree of governance and low levels of corruption. Moldova has a CPI score of 42, which ranks it 76th out of 180 countries. This ranking takes into consideration a wide range of illegal and unethical activities within the public sector, including bribery, nepotism, diversion of funds, and state capture by vested interests.

Estonia ranks in the 91st percentile on the World Bank’s Government Effectiveness Index, which measures the efficiency of government services, public sector regulations, and public administration. Moldova ranks in the 46th percentile, indicating a government that struggles to establish and maintain policies that are of benefit to its people.

Estonia is ranked 10th globally on the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, which measures the extent to which the rule of law is observed in a country. Moldova is ranked 64th globally, indicating a lower level of fundamental rights, rule of law, regulatory fairness, and transparency. In particular, WJP notes that Moldova’s criminal justice system is both ineffective and corrupt.

Estonia ranks 7th in the world on the Economic Freedom Index from the Heritage Foundation. This indicates a pro-business environment with low levels of regulations. Moldova ranks far worse, at 99th in the world. This indicates endemic corruption, a high level of government spending, and regulatory inefficiency.

On the Human Development Index, Estonia has a score of 0.899, ranking it 31st out of 190 countries. This indicates high life expectancy, a well-educated populace, and moderately high income per capita. Moldova has an HDI score of 0.763, ranking it in 86th place. This score reflects slightly below-average life expectancy, but a fairly high level of education, and per capita income that, while low by European standards, is above the global average.

Estonia has a Global Peace Index score of 1.615, ranking it 24th out of 163 countries. This score considers 23 different indicators, ranging from violent crime to external conflicts. Estonia performs well in most categories, but tensions with neighboring countries bring down the total score. Moldova has a GPI score of 1.976, ranking it 63rd worldwide. While still relatively peaceful by global standards, Moldova suffers from the same regional tension as Estonia, while experiencing worse criminality.

What This Means for the World

The stark contrast between Moldova and Estonia is a timely reminder of what was consensus opinion for most of the world during the last three centuries: government intervention into society and economics produces worse outcomes than those obtained by individuals acting freely.

Today, the UN is calling for “sweeping societal transformations” driven by strong governance, and the World Economic Forum is proposing initiatives such as “The Great Reset,” which imagines a future with unprecedented government interventions aimed at mitigating climate change and income inequality. In doing so, these entities seem to be returning to the ancient Platonic ideal of the philosopher-king, while discounting the intervening millennia of authoritarian oppression and abuses.

As officials consider implementing these big-government policies, they would do well to remember that, no matter how well-intended they may be, two thousand years of history – and the recent experience of two small post-Soviet states – provide ample evidence that it is far better to err on the side of too little governance than too much.

wull, I Mulled'Ovah yer question... clearly Moldova (Mauled Ovuh?) is one dumpster fire from Hell (ah, that viddeyo wuz sumthin') but.... Estonia? It's all told one big SMART CITY an' even the president calls it "Little Sister" (they spy on their citizens LOTS, they have digital ID, but Big Brother is "benevolent"...an' that's OK until ye gitta not so benevolent leader in place)...

They also track citizens by the chips in their smartphones--EVERYTHING is SMART there... "velly schmart Max"--imho that means Kaos! is simply BEHIND the wall/paywall/in yer schmart light (bugs!)....

https://www.liberties.eu/en/stories/privacy-violated-estonia/13795

and....

https://estonianworld.com/security/president-ilves-big-brother-vs-little-sister/

My answer? neither... (plus who speaks Estonian?) but I'll argue that the while MoldOver is soitenly showin' it's ugly inside on the outside (the perils of communism...), Estonia ain't no picnic (tho' likely those that say "they have nothing to hide" work for the gubbamint there).

OH many/most chobs online.

Methninks this litte "burg" (a country the size of New Hampshire) works too as it's small an' has a mostly homogeneous population... folks culturally, ethnically, an' otherwayz alike--even if we scratch out the last X no. of years in "AmeriKa" with the MyGrunts, we have a far more varied nation--urban/rural/suburban/ ethnically & religiously mixed.... our can of worms that would mean "botch-u-lizz'em" in the USA.

I lean libertarian myself but a technocracy? nah...