The backstage area was dark, lit only by the glow of video monitors. Out there, on the other side of the fire-retardant curtain, somebody was giving a TEDx talk. It wasn’t the one about people having sex in an MRI machine for science – I remember that one. It also wasn’t the one about bowel movements that made half the audience line up for the bathroom afterwards. It was one of the less memorable ones. I was home from college for summer vacation, and as a film student I occasionally got the opportunity for freelance work on one-off productions like this.

During this particular job, my wisdom teeth had started acting up, and I was eating Advil like candy. The tight, heavy headset squeezing my skull didn’t help. I watched the director’s status monitors: the big ones were “program” - the feed being recorded, and “preview,” the camera angle that was about to be switched in. The other monitors showed the signal coming from each camera, as the operators set up their next shots.

“Get me a decent crowd shot, for God’s sake,” the director hissed into his microphone. I heard his voice in my ear, as did everyone else backstage. We were all wearing the headsets, and we weren’t supposed to talk unless we had a good reason to; only the director’s whispered commands were supposed to be heard.

Through the monitors, I saw the cameras zoom in on various sections of the audience. This was in the days before smartphones, so people were more attentive than they are now, but, nevertheless, there was something wrong with every shot. This guy was asleep, that one had some kind of facial deformity, and everywhere there were women chewing gum.

Those who have never worked in video production have no idea how much of an issue gum-chewing is. In person, it doesn’t look like much of anything – just a nondescript, common behavior. But through the camera, it looks exaggerated, like a cartoon cow chewing its cud. Directors hate it. And women are, by far, the worst offenders.

The director was getting annoyed. He’d been sitting on a shot of the speaker for too long; on a production like this, which doesn’t have much inherent visual interest, you want to switch angles every few seconds to keep it interesting, and this was dragging on.

The struggle to find a visually acceptable group of people continued. The cameras slowly panned the crowd. Sleeper, gum-chewer, reader, gum-chewer … No joy anywhere.

The director grunted. He gave a heavy sigh and ruefully commented, “If women liked cock as much as they like gum, we’d all be a lot happier.”

The backstage area - normally silent as a tomb - quietly erupted with the barely-stifled sound of men choking back laughter. For a moment, I forgot the ache in my jaw and the fact that the rest of the crew was older and more experienced than me. In that moment, I was just one of a bunch of guys professionally focused on trying not to laugh out loud at a wildly inappropriate comment.

I haven’t worked on a live production for many years. I suspect that these days, “locker room talk” is a lot less common than it was in the days before #metoo. But, in a nutshell, that’s the kind of thing that happens behind the curtain of every media spectacle, whether it’s as small as a local TEDx talk or as big as the Superbowl. Just as every glitzy high-rise building has a sweaty, grizzled guy in the basement keeping the whole thing running, every high-end restaurant has people who can’t speak English washing dishes (and maybe cooking too), and every organization relies on stressed-out nerds to keep its technology functional, the sleek, polished architecture of media rests on the backs of an army of foul-mouthed guys wearing black t-shirts and tight headsets.

I spent about two decades working in digital media. I had gone to film school so that I could be the next Robert Rodriguez – make a brilliant short film, get discovered by Hollywood, and become a big-time director – but apparently thousands of other film-school grads had the same idea. Plus, that career trajectory only works if you’re actually Robert Rodriguez.

So, too snobby to do wedding videos, I settled into a career in commercial production. Not big commercials, like Nike or Burger King, but small commercials, like local car dealers and grocery stores. For much of that time, I was sort of a hired gun; advertising agencies that didn’t have in-house production facilities would hire me to film things for them. It worked pretty well (until 2008, as I’ve written about previously), because I didn’t have to go out and find new clients, and as long as I stayed behind the scenes, the agency folks took on both the risk and the reward.

I was not an artist, I was a creative technician. In mythic parlance, I was a low-status wizard; not Gandalf, not Merlin, but Schmendrick: skilled enough to amaze the bumpkins who visit the carnival, but not the first person you’d call to deal with your kingdom’s dragon or zombie problem.

There’s something to be said for a ground-level view. The butler always knows where the bodies are buried, the housekeeper always knows what everyone does at night, and the carnival magician knows how the smoke and mirrors work. In my case, I saw first-hand how narratives are shaped and illusions are maintained.

There were the New York producers who came to town after 9/11 to do an éxposé on a Southern steel plant allegedly profiteering off World Trade Center steel by making it souvenir coins. In reality, when the mangled beams from the Twin Towers had been dragged in to be recycled, the men – hardened, salt-of-the-earth men from rural South Carolina – recognized, with tears in their eyes, that this was not metal that could be turned into brake parts and dog food cans. They decided to honor the sacred sacrifice it represented by smelting it into commemorative medallions, charging just enough to cover their costs.

But, as I sat silently, monitoring the audio levels during the CEO’s interview, I heard his anxiety, his inexperience in dealing with the media; he was telling his story, but not in a way that smoothly fit into a soundbite. The correspondent was visibly touched by the truth, and promised to make sure it was revealed. But when the story ran, it was the way that headquarters wanted it: the ignorant, greedy Southerners making money off New York’s collective trauma.

Or the dermatologist, who had been asked to film a medical commercial about skin safety. On camera, she read the provided script, encouraging people to go to their dermatologist for a yearly checkup. As we were packing up, she commented that seeing a patient once a year made it very difficult to spot changes, and that “nobody knows your body better than you do.” If we thought something was wrong, she said, we needed to be our own advocates: even if the doctors didn’t think it was worthwhile, make sure they took it seriously and checked it out. That, I thought, would be a much more useful PSA, although not one the hospital would be likely to sponsor.

Experiences like this have given me a nuanced view of how the world operates. I am skeptical of large-scale conspiracies, because they would require too many unreliable people to stay silent, but I am well aware of the countless tiny deceptions that are simply “business as usual.” Also, as with the director’s dick joke, a lot depends on reading the room. Is it a conspiracy if people discuss it openly, but only in certain environments? From what I saw, that’s how media, government, and every other system and organization work. Where do privacy and confidentiality turn into deceit and collusion? It’s not a clear line; it’s a fuzzy one, with many shades of gray.

I was a low-level wizard; not the kind who orchestrates magnificent illusions for an audience of millions, but the kind who conjures his neighbor’s dreams, fear, and greed into reality for a handful of coins. From where I stood, I could see how the scenes were set and the strings were pulled, even though the actual decisions were being made high above my paygrade. But there’s a sense of honesty behind the curtain, a feeling of pride in the craft of fashioning illusion. The show must go on.

These days, I feel differently. Like Schmendrick, the carnival lost its appeal for me once the unicorn showed up. Maybe it was in 2008, when the theatre burned down. Or maybe it was in 2020, when I saw the tricks of the trade being used to destroy society.

I don’t know if the world changed, or I did. But I know that there are thousands of others like me who are still keeping the scenery moving and the laugh track playing. Guys in black t-shirts snickering into headsets, producers, assistants, and flacks: a legion of professionals who never quite made it to Hollywood, but who found a place in the crew that broadcasts this thing we call reality to the masses.

Sometimes, reality is weird: like the way you can find people willing to have sex in an MRI tube, or make a hundred people want to go to the bathroom just by talking about bowel movements. Sometimes, it’s sad: like the way well-intentioned acts can be misinterpreted by those who feel harmed. Sometimes, it’s scary: like the way doctors will say one thing on camera, and another when the camera is off. But most of what we know of reality today does not come from our personal experience; it comes to us through flickering images and far-off voices housed in magic boxes.

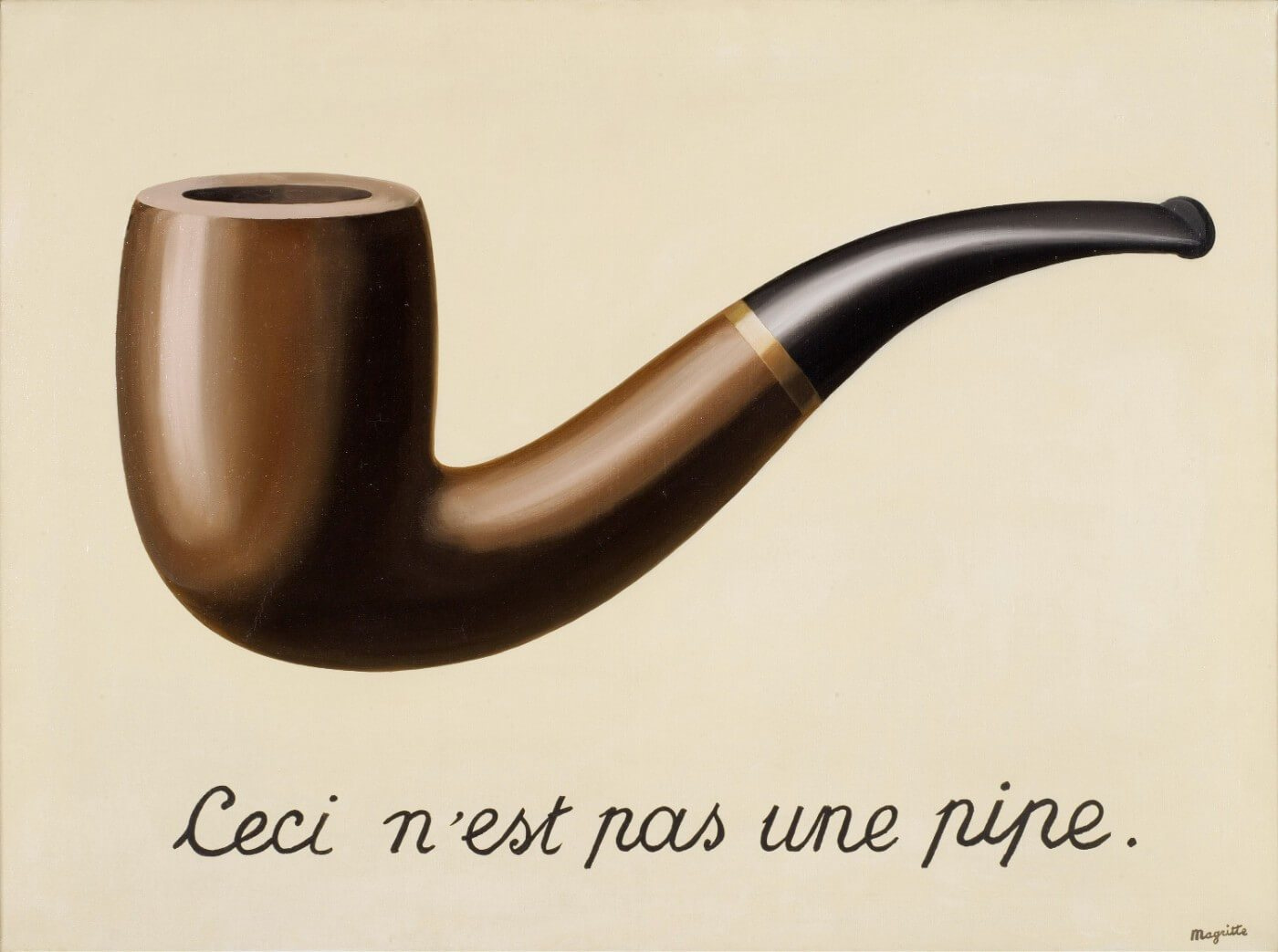

We’ve grown so accustomed to this everyday magic that we don’t even recognize it anymore. A century ago, René Magritte painted a realistic picture of a pipe and captioned it, “This is not a pipe.” His point was that a representation of a thing is not the thing itself. The mirror we hold up to reality – the cameras, the media platforms, the technology – do not contain the world, they merely flatten and curate it to fit the frame. The gum-chewing women and sleeping men are not shown, the ugly and the infirm are kept out of sight until they can be used to provoke an emotional response, and the nature of that response is carefully determined in advance by unseen operators.

I’m no longer a low-status wizard, but I’m certainly not a high-status one either. Halfway (hopefully only halfway) through my life, I’m not sure what I am, or what I’m becoming. But I do know that I’ve had enough of puppet-masters and stage managers; stifled laughter and sawdust. As our experience of the world becomes increasingly mediated by glass screens and magic mirrors, I find myself wanting more of what’s truly real, honest, and meaningful. And I don’t think I’m the only one.

Wow—this is powerfully written. The disillusionment of the illusionist is about as real and raw as reality gets. Thanks for putting this all down in such an eloquent story. I suspect your reflections here will resonate with many of us who have been likewise disillusioned.

Rang close ta home fer me as well Alex... yup, livin' in the "real" is key--it's (howevah) whut permits us ta tell stories on paper, on screens (silver preferred!) an' even thru ahrt, moosick, etc. Too many I met (not so much "crew" 'er mah fellow "acteurs" but those show runners an' higher uppers) are too distanced from real life... One tangential tale I gotta cover...it's the MBAs that infiltrated the film biz--try pitchin' ta guy in a $5K suit who ain't never seen Citizen Kane. Raisin' my hand fer that'un! Yup.... lotta these folks have their heads up their hineys! They live atta different altitude (an' with a diff. attytude too)

I've woiked high-brow an' low brow (an' a few weddin's too lol)....

Now that 9/11 coin tale ya shared is sad....

I NEVAH seen quite so egregious a slime dun on anyone decent but I did work on sum' talkin' heads shoots whar they made sum'buddy appear ta project a totally different viewpernt via the edit (cut-aways, etc). I'd say lies are frequent an' tho I love Magic Shows & the "illusion" of Cinema/Sin-e-ma, sum thangs do go beyond expected "tricks of the trade" an' venture inta dishonest portrayals.... I 'member bein' on set for products that didn't work no-how such that ya needed ta take dozens outta boxes ta git one that warn't a lemon. Those in charged fudged. They shot from the one angle, ya didn't see the unfinished back....

As a PA (pre inside props!--mah far better/better paid gig along w/ actin') I held the slop/spit bucket fer an 8 year old "Lil' Caesars pizza eater" who never swallered one bite of the junk food he appeared ta love on camera. I also help float cereal one piece atta time in milk made've Elmers Glue (gallon jug) so it floated. Fer a feature I helped assemble "ice cream cones" from dyed mashed taters.... an' more! Some of it wuz fun...much tedious tho! I watched food stylists blow-torch a giant RAW turkey an' made it look like a Norman Rockwell/Hallmark special! (After puttin' corn syrup with dye in it on ta glaze / carmelized it). Yum? Nix. (fwiw, you cannot alter the product yer sellin' but you don't have ta eat/use it (this might've changed but many celeb. sponsors had no clue 'bout the products they wuz sellin'/shillin' fer ) an' anythin' else on the set is fair game ta alter.

PLUS ya kin pick out the best parts! Imagine the one Burger King boiger you see on the teevee wuz Frankenstein assembled from 100! many bein' full out discarded... One non-wilted flower Boo-Kay assembled from 40 on set. WASTE is also a thang on commercials 'specially. Not so much features ('specially the lower budgie ones).

IF it's any consolation... Schmendricks abound at all levels! I've been a fly on the wall both in front'a an' behind the camera via extree/walk-on/bit work an' "inside" props (on bigger gigs) wuz my bread 'n butter fer years an' that'd include features, commercials, industrials, PSAs, moosick viddeoys an' more--so much ya say is close ta home fer me. Lowerz on the food chain bein' asked ta "cover" fer uppers (some on uppers! lol), screw ups galore--adult tantrums, nepo hires acti'n all unprofessional-like, the woiks!

Tho' the locker-room banter wuz not so hilariously jawr droppin' round the laydeez (I'd a spit my cawfee too), the "lite" lewdness (fwiw) at the warter cooler tended ta come from the IA (IATSE) major union jobs than on the NABET (then indie union) gigs where the men-folks got paid less an' were genuinely waay less old skool Longisland (one woid) sexist types... I did hate bein' called "honey" all the time then tho! (double-edged, again, not by the NABET fellas, most such sweeties). But I DO know eggzactly the type've stuff ya woiked on.

I'm also sad that so many--Kubrick & Welles come ta mind--had ta suffer such dramatic cuts ta their werk due ta the MoneyMen... the former likely lost his life objectin'! So yes, trooths are mischaracterized all the time, performances are "cut" ta render totally diff. pov's, an' sum shows start out with an agenda of lies.

This is why I prefer stuff where the audience comes in KNOWIN' they'll see a Magic Show or delightful illusions--Méliès!!!!

But don't fergit--many've us Shmendricks are still tee-riffic story-tellers in spite of not bein' the next Robert Rodriguez 'er fer me it wuz the Coen Bros--I git it! Substack's our book deal--an' micro productions are now possible (yup I hate diggy-tale but there IS sumthin' ta doin' stuff on the cheap) so don't put down yer wand Alex.... there's GOOD magic too ;-) (with a nod ta the GREAT Houdini / Erik Weisz!)