I went to art school, and I am an art snob. Granted, I was a film major, so in a classic instance of “Those who can, do; those who can’t, criticize,” I’m much better at pointing out what’s wrong with someone else’s painting than making my own. Nevertheless, the blitzkrieg of “generative image” AI compels me to set my snobbery aside and make an impassioned plea for the kind of ill-conceived, poorly-executed creative endeavors that would normally be the target of my withering condescension.

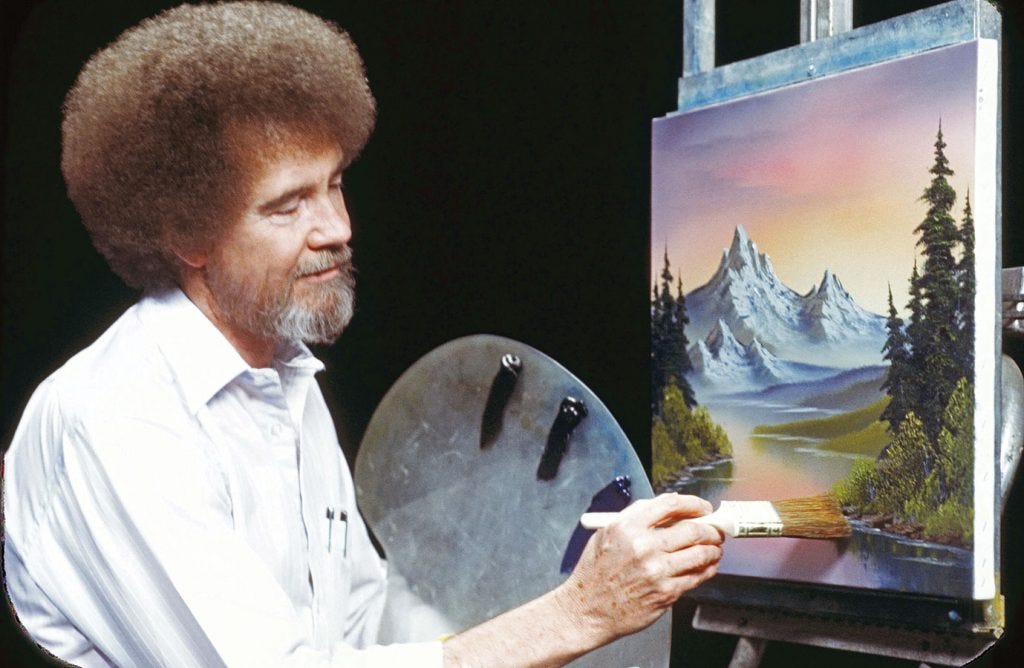

In fairness, I usually reserve my disdain for work that’s hanging in galleries (often with one or two unjustified zeroes on the price tag). When it comes to purely amateur art, I have a soft spot. As a kid who grew up struggling to paint along with Bob Ross and to draw comics the Marvel way, I learned first-hand how difficult it is to make something that actually looks good.

As I observe the synthetic professionalism of Dall-E and Midjourney, it occurs to me that these platforms produce something other than images. They manufacture a sense of futility. Why should today’s 12-year olds spend hours struggling, as I did, to draw a wizard with a crystal ball, when they can log onto NightCafe and have nine variations done within seconds?

Setting aside the bizarre (and ostensibly temporary) difficulty that AI has with drawing hands, why should anyone, of any age, put effort into depicting something that’s in their mind’s eye, when there’s an app for that?

Crucially, this question extends beyond the world of visual art. With AI now capable of competent writing, passable design, and occasionally tolerable music composition, it’s difficult to explain the value of doing something badly for yourself when a machine can do it well for you.

Because I love irony, I told OpenAI to make this case for me. Here's what it said:

The rise of machines has led many to question the value of human creativity. However, the act of creating things is essential for human flourishing. While machines can certainly produce things faster and potentially more efficiently than humans, they cannot replicate the emotional and personal benefits that come from the act of creating. Engaging in creative activities such as art, music, and crafts can be a deeply fulfilling and enjoyable experience that promotes personal growth, self-expression, and can make a positive impact on the world. By creating something unique and personal, individuals can leave a lasting mark on society and connect with others in a meaningful way. The power of human creativity cannot be underestimated, and it is essential that we continue to value and prioritize it in a world dominated by machines.

As with most AI-generated content, this is okay as far as it goes; it seems a little patronizing to me, but perhaps that’s just because of the “world dominated by machines” bit. In any case, it’s as dry as day-old toast. That’s because, no matter how technically proficient a machine is at mimicry, it can not speak from the heart. A machine creates because it is told to accomplish a specific goal. We, on the other hand, create, not as a means to some other end, but because the act of creation itself is vital to the human experience.

“Vital,” by the way, is derived from the Latin word vitalis, meaning “of or belonging to life,” or “essential to life.” For those of us (and I believe this is most people) who feel the need to create things, that urge is indeed essential to life. It also does, in my opinion, belong to life. We sometimes forget that machines do not have any of that. They can mimic life, but they are quite literally dead inside.

That’s the supply side of the equation. We create because we must. But there’s also a demand side; we crave items that are created by other people. And not just art. The industrial revolution replaced commercial handcrafts like weaving and pottery with machines that could crank out cloth and crockery with greater speed and consistency than any human, but, over two centuries later, there are still shoppers interested in handmade textiles and ceramics. In fact, they’re now considered luxuries.

Why is this so? Why pay extra for something that takes longer to make and is less perfectly crafted than an equivalent, machine-made item? I would argue that it is because human-made objects have soul.

When a person - a living, flesh-and-blood human - directs their energy into making something tangible, an ineffable imprint of their humanity is locked into it like a fingerprint. Look at a piece of Meiji pottery, a Rembrandt painting, or an African tribal mask. You will see within it, glimmering as faintly as a distant star in the twilight sky, the essence of the person who conceived it and brought it into being.

AI, on the other hand, has the fingerprints and soul of a latex glove. Functional, yes. Enchanting, no. It can be useful, and even impressive, but it can never imbue its work with more than superficial meaning.

One could argue that, even judged by a purely technical standard, a Rembrandt painting is better than anything an AI can produce. But that may not always be true. The technology is evolving rapidly, and it would be unwise to predict where the ceiling will be.

That’s why I believe it’s important to defend amateur art. Most hobbyists can’t draw better than Midjourney. This may be discouraging to them, but it most certainly does not mean that their endeavors are in vain.

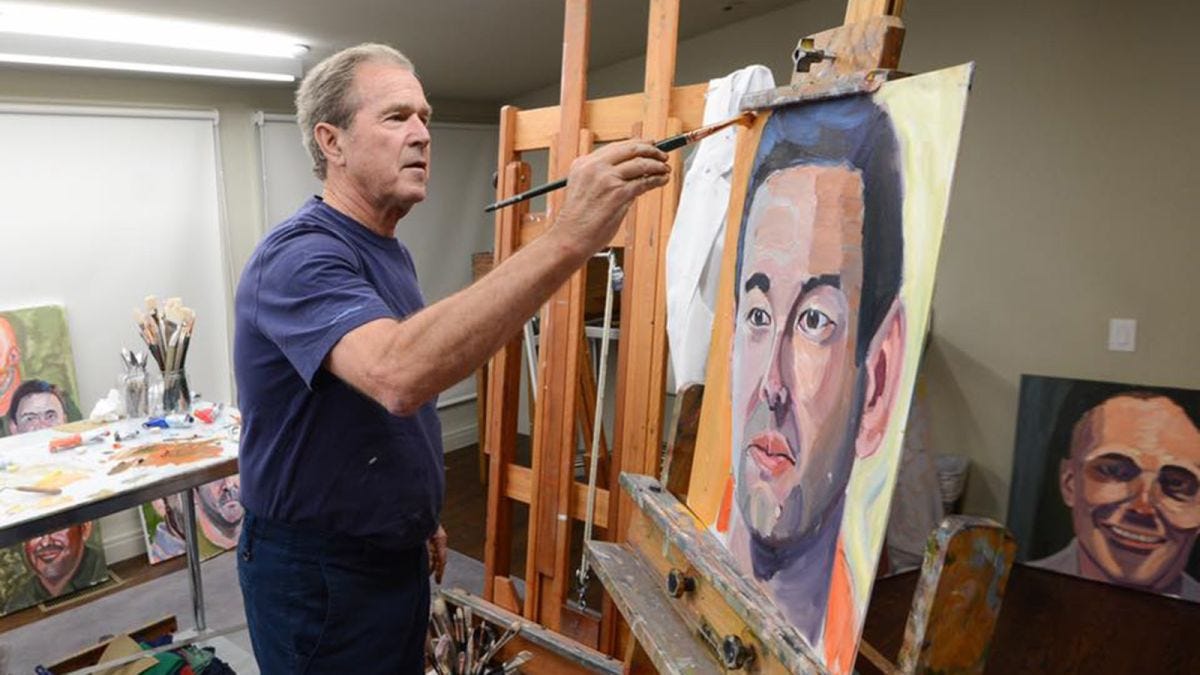

I’m no fan of George W. Bush’s art, but the results of our ex-President’s avocation provide a perfect example of what I’m talking about. George is an avid - and unequivocally amateurish - painter. Still, if you look at one of his technically unsophisticated canvases, you see his humanness. It is the work of a simple man who, because of an accident of birth, was thrust onto an iron throne he never seemed to want. A man who was reading a book to children when the 9/11 attacks struck. A man who, whatever you may think of his politics or his fitness to lead, has to live with the knowledge that, as commander in chief, his decisions resulted in the deaths of thousands. The experiences and memories of a lifetime are reflected and transmuted into his lumpy brushstrokes, dissonant color choices, and ill-proportioned figures. The work is significant not for what it is, but for what it represents: a human soul striving to express itself.

As celebrity artifacts, Bush's paintings may have monetary value, but as objets d’art their worth is identical to the toddler-scribbles that every parent hangs on their refrigerator. The objective quality of the product is irrelevant; it is the act of creation - no matter how crude or devoid of talent it may be - that is important.

At the professional level, value can be complex to calculate; artistry and craftsmanship are inextricably bound to creativity, but channeled through considerations of commerce. At the amateur level, it's much simpler. The work matters only because we matter. We matter to each other, we matter to ourselves, and - if you are a believer - we matter to God.

Consider a muddy watercolor portrait of the family dog painted by a seven-year old. It is precious, not because it looks amazing (it probably doesn’t), but because her love for the dog was inside her and she let it out into the world. Maybe it only took her two minutes, and maybe it looks sort of like a green blob, but she wanted to make it real, and she did. Even if the painting slips off the fridge, gets stepped on, is crumpled and ultimately discarded, that little girl seized the opportunity to create something meaningful to her. In some tiny way, doing so contributed to her development as a human being.

Ultimately, the question AI forces us to ask is: why is our humanity important? There are two ways we can answer that question. Like folk hero John Henry, we can define ourselves by our functionality. And, like him, we can work ourselves to death trying to outperform machines that are stronger and faster than us. This train of thought leads to nihilism. If we are what we do, and machines can do it better, then why should we bother to do anything at all?

The alternate approach is to reject that narrow, utilitarian definition of our being. Instead, we can recognize that we have intrinsic worth apart from what we produce, but that there is also value in the authenticity of what we write, draw, compose, weave, and otherwise bring into the world. When we, as human beings, make things, they emerge from somewhere deep inside us (or, if you prefer, from a higher power), because we made the effort - however imperfectly - to breathe them into existence. Like the child’s portrait of a puppy, it’s not the product that counts, but the process.

It makes no difference to a computer whether it draws a picture, composes a symphony, or sits idle. Machines do not create to live, nor do they live to create. From toddlers to ex-Presidents, we, as human beings, do both. We are driven to create and share things that are meaningful to us, and we are attracted to things created by others - especially by people we care about. It is a fundamental part of what it means to be human.

Regardless of how far AI progresses, it is still merely Artificial Intelligence. The intelligence part may be open to debate, but the artificiality is not. No matter how convincing its simulation of humanity may be, synthetic creativity is just that: synthetic. It is inauthentic, fabricated, and one pixel deep. Toddlers and ex-Presidents can take heart; no matter how many things a machine can do, it will never be able to do any of them with soul.

Many of the same arguments can and have been said about penmanship, justifiably so. One thing said about penmanship vs. typing on a keyboard applies here too, but perhaps in a slight different way. The difference between writing “A” and “B” are far greater than the differences typing the two. The process of learning how to write by hand, especially cursive, is far more demanding than that of typing. The differences in mental commands and muscle control between writing letter is far greater than those required for typing. Thus training in penmanship creates greater hand and eye coordination as well as developed the not only the mind but also the physical structures of the brain in ways different from that of those who start off on a keyboard and do not learn penmanship.

As penmanship has long been dropped as a required part of the curriculum in the US and Great Britain, many college and university graduates from the two countries can neither write nor read cursive hand writing. Their brains are, in fact, different from those who can read and write in cursive.

On the soul vs soulless argument, which do we all prefer, a hand written letter of an email, or even a typed letter in the mail? The author of one of my favorite historical books makes it a point to not just read the text of writings by the subjects of his work but to, whenever possible, hold in his own hands the letters, cards and notes written by the person. The example he gives is of a letter a disgruntled constituent wrote to a politician he would later murder. Only with holding the actual letter in his hand could he see the force the writer exerted upon the writing instrument and the paper, emotion that is lost in the sterile, typed version of the message found easily online.

I believe this is by design. Mailing packages to the US from overseas now requires a printed label, handwritten addresses are not longer allowed. Machines can’t read handwriting with consistent accuracy.

couldn't agree more as a classy-cull ahrt fan embracin' both hi an' low (lois too..)

only thing I cain't stand is (f)ahrt--the sorry peecee but lousy stuff the WhitKnee sticks in it's embarrassin' Bea-an'-Ollie white-wall-tired joke've a show now'days

near n' dear ta me are velvet paint by numbers an' thrift store porte-ritz (!)

An' tho Dabbler DubbaYa's (f)ahrt lands a bit low in the barrel, I will say that other celebs give me a grin bigger n' a jack-o-lantern--Fer example, a doozy from the GREAT Tony Bennett:

https://tinyurl.com/kfnz377v (Mickey we hardly knew ya!!!!)

I hate AI in all forms (I cut it no slack like some'a my pals even). (So the cheeze stands alone!)

FWIW,my younger daughter who iz a classy(cal) ahrtiste (purdy good too!), agrees with ya on Mista Ross--he makes it look easy but fer a young'un it ain't easy at all!