Is the Internet the Second Coming of Radio?

Today's online creators are a lot like last century's broadcasting pioneers

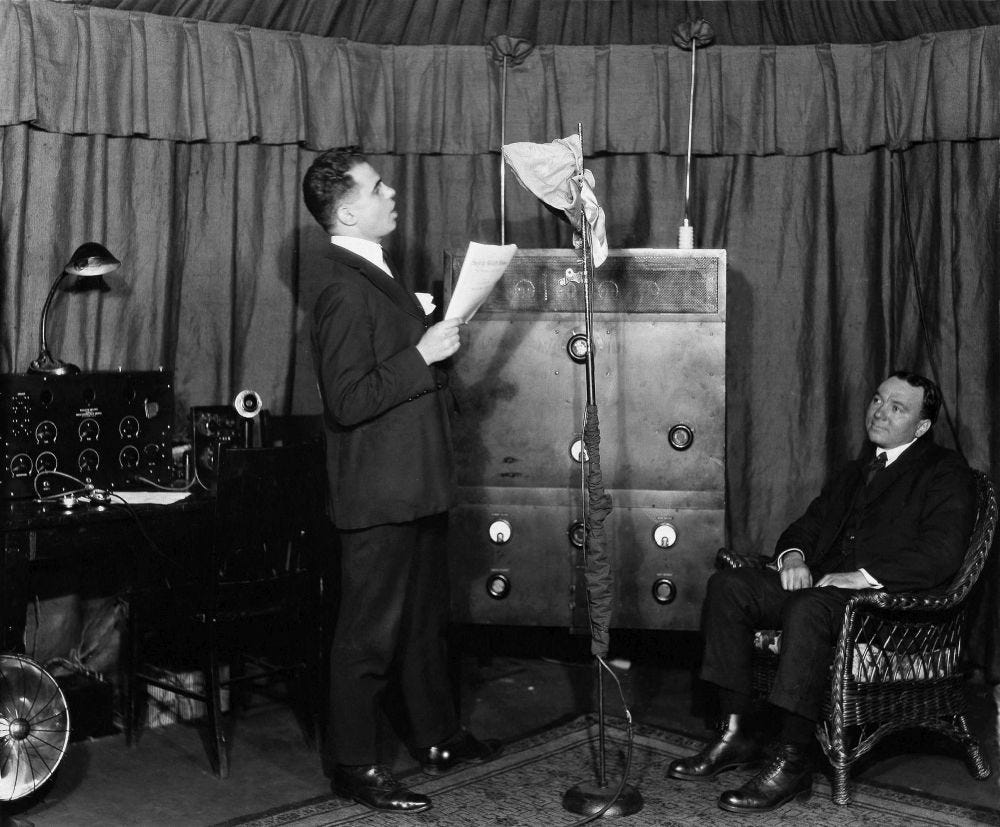

Almost exactly 100 years ago, a motley assortment of artists, technicians, and entrepreneurs launched a movement that transformed American life forever. In many ways, the unconventional personalities and innovative spirit of those early radio broadcasters - as well as the way that corporations and bureaucrats rapidly asserted control over the fledgling medium - directly parallels today’s online world.

Since radio’s invention in 1895, it had been used primarily for point-to-point communication. First, this was done with Morse code, but during the WWI years, the U.S. Navy developed (and patented) the technology required to transmit voices and music. In October, 1920, the Westinghouse Corporation was awarded the very first U.S. commercial broadcasting license from the Department of Commerce, and on November 2, 1920 transmitted the first commercial broadcast, using call sign KDKA in Pittsburgh, PA.

The radio revolution started quietly. Over the next two years, a handful of small, low-power radio stations popped up around the country, and what we would call “early adopters” went out and bought radio receivers for their homes. Then, in 1922, the slowly-growing snowball turned into an avalanche. The number of stations exploded from 28 to 556, and shoppers bought more than $60 million of radio equipment - that’s over $1 billion in today’s money, which is comparable to what Apple netted on its first-generation iPhone between 2007 and 2008.

Just as with the nascent internet in the 1990s, people in the 1920s weren’t exactly sure what to do with the new technology once they had it. Well-funded, high-powered “Class B” stations that could cover a large city were few and far between. Most transmitters were operated by “Class A” stations that could only be heard within a small town or a city neighborhood. This meant that, for those with the vision and drive to take to the airwaves, the opportunities were endless.

From 1922 until the mid 1950s, when TV took over, the national radio waves were a free-for-all of every kind of content you can imagine. Big, Class B stations aired slickly-produced news and sports broadcasts, along with game shows, soap operas, and elaborate radio plays, but the little, Class B stations produced content that was very similar to what’s on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok today: musical performances, advice programs, comedy skits, kids’ shows - most of it made on a shoestring budget by tiny, dedicated teams, and almost all of it produced live, on-air, never to be heard again.

Generations before the internet created an accessible platform for marginalized groups, the airwaves were home to programs produced by and for the diverse residents of the American melting pot. New York City was home to a plethora of Yiddish-language stations that catered to its Jewish community. Spanish-language stations proliferated across the American Southwest. Atlanta was home to WERD, the first black-owned radio station. For immigrants and minorities who were either invisible on mainstream radio, or depicted with degrading stereotypes, these local stations provided a mirror in which they could see their own culture, experiences, and values reflected with authenticity and respect.

"If a speech by the President is to be used as the meat in a sandwich of two patent medicine advertisements there will be no radio left."

- Herbert Hoover (then Secretary of Commerce), 1924

In much the same way as corporations and regulatory agencies colonized and commercialized the internet, the free-wheeling early enthusiasm of radio was rapidly dampened by the authorities of the day. Although public officials were wary of the negative influence that advertising might have on the public interest, it soon became clear that advertising was the only way to finance the constant stream of content that live programming required.

As soon as the money train started rolling, the dirty tricks came along for the ride. In 1923, AT&T - whose vacuum tube patent made it a key player in the radio industry - tried (albeit unsuccessfully) to monopolize radio by building a nationwide network of stations and forcing little operators out of business. Four years later, under pressure from NBC and CBS, Congress created the Federal Radio Commission, which, in an early example of regulatory capture, promptly started shutting down the large broadcaster’s small, local competitors.

Under pressure from unscrupulous corporations, corrupt politicians, and competition from the new marvel of television, the golden age of radio wound down in the 1950s. While the early decades of TV did provide an outlet for unique visionaries like Rod Serling and Gore Vidal, the cost of television production created an almost insurmountable barrier to entry for the amateurs who had shared their quirky talents through Class A radio.

Look past the modern veneer, and you’ll see that online creators have a lot in common with their antecedents. Podcasts like Welcome to Night Vale are almost indistinguishable from the radio dramas that captivated our great-grandparents. YouTubers like Mr. Beast and Nigahiga use video, but it’s easy to imagine them bringing their schtick to Depression-era listeners. Likewise, it’s intriguing to consider what someone like Victor Packer - who personally created sixteen different 15-minute programs every weekday from 1930 to 1942 - would do today with a laptop computer and a smartphone.

At its worst, the 21st-century online world exerts a destructive influence on its users - particularly young people. It also provides fertile ground for corporate exploitation and public graft. But, at its best, it provides a platform that echoes the unfettered creativity of radio’s golden age. Anyone with talent and motivation can share their ideas with a global audience, at virtually no cost. It’s an opportunity that the neighborhood broadcasters of the 1920s and ’30s could never have imagined, but would certainly appreciate.

Though not that old, I have always preferred radio to TV. One of the local stations attempted to bring back the golden era of radio you write of either in house or syndicated. This would have been in the 80s. I loved it. One aired reruns of “Chicken Man” which left me in stitches as a child. Later, in the year 2000 I was working in the South and heard several radio story shows. My favorite being, “Married Man”. Whenever I have heard a recording of any of the old radio story programs, I have always been captivated by the quality of the stories, voices and sound effects.

Except, that the platforms needed to air their work will shut them down the moment they are naughty, like saying that masks will not stop an airborne virus.