In the days before social media, it was customary to share one’s opinions by displaying bumper stickers. A popular message was, “If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention.” What the reader was supposed to be outraged about was never specified. There were, the sticker implied, lots of outrageous things out there, once you started looking for them.

Today, we don’t have to go looking. Outrage-provoking information tailored to our personal worldview is automatically delivered to us on every available screen. Whether it’s Donald Trump or the Deep State, climate change or border security, the Middle East or Ukraine, everyone seems to be upset about something.

But what is all that anger and frustration good for? Or, to put it another way, what are the results of our outrage? Even if it’s justified, does it fuel positive change, or is it just self-indulgent, impotent fury? More importantly, what does it do to us individually and societally?

The sad truth is that media conglomerates, tech companies, and the people provoking our anger all benefit from our addiction to outrage. The more we run around with our hair on fire, the more we stay glued to our screens and the less genuinely productive action we take.

Brief madness

Roughly two thousand years ago, the Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote a treatise about anger in which he argued that “no plague has cost the human race more.” In his view, anger is a pernicious “brief madness,” providing a seductive illusion of control to people who have, in reality, no control, even of themselves.

To ward off this madness, Seneca urged his followers to avoid provocation, to pause instead of reacting impulsively, to reflect on the underlying causes of angry feelings, and to seek the company of level-headed peers, “since they’ll neither provoke your anger nor tolerate it.”

It took two millennia, but modern neuropsychology has validated Seneca’s conclusions. What he called “passion overpowering reason,” we can see in an fMRI machine as the brain diverting resources away from the prefrontal cortex (where rational thought is based) and toward the limbic system (the home of fight-or-flight survival instincts). Strong emotion does, indeed, overpower our ability to think clearly, triggering us to act in ways that are predictably harmful, both to ourselves and others.

Similarly, just as Seneca observed, research has shown that the anxious and angry feelings associated with outrage do give us an illusory sense of control over situations in which we have no control. While anger can sometimes be rooted in emotions such as shame, loneliness, and sadness, it is a often response either to a perceived threat, or to not getting what we want. When we can’t actually do anything to mitigate the threat or rectify the situation, worrying or ranting feels like doing something.

These feelings of powerlessness are tremendously amplified by modern communications technology. As Neil Postman observed in Amusing Ourselves to Death, for most of human history, we only heard about events that had an immediate impact on our lives or communities. Today, we are flooded with information from across the globe, about which we can do nothing. Our poor brains, which essentially stopped evolving in the Stone Age, have no idea how to handle this.

In other words, the likelihood of you or I having any impact on a foreign policy we disagree with is virtually nil, but because our screens put the issue directly in front of us, our brains feel compelled to respond in some way. Confronted by information-age technology, anxiety and anger are the best our Neolithic brains can offer.

Rage is counterproductive

Unfortunately, once our brains get into the habit of producing anxious and angry feelings as a response to the stimulus of news and social media, it’s very difficult to respond in any other way. Technology has trained us like lab rats to lash out when provoked.

Even worse, like any other kind of addict, we seek out material that will give us another fix of those “feels-like-doing-something” emotions. Just as Seneca warned, this further reduces our ability to think rationally and control our own behavior. By becoming trapped in an impotent rage spiral, we’re not helping anyone and only hurting ourselves.

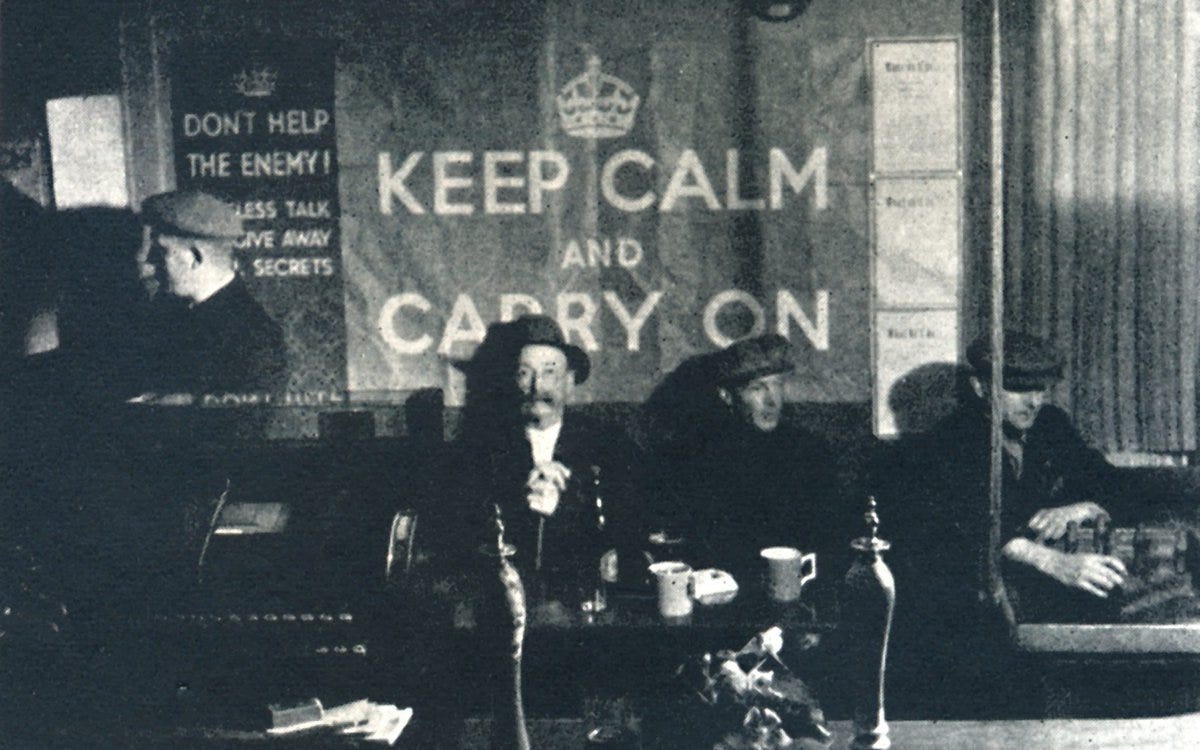

Ironically, the angrier we are about the powers-that-be, the easier we are to control. The more upset we are, the more our limbic system stays activated and our rational faculties stay suspended. This is why well-intentioned leaders encourage their people to stay cool in the face of adversity, while tyrants inevitably stoke the fiery social contagion of fear and anger in their populations.

So, what’s the way out of this rat trap? Contemporary research agrees with Seneca: psychologists recommend limiting our exposure to unneccessary and provocative information, consciously choosing to pause before responding to such information, associating with those who prefer rational discourse to emotional outbursts, and becoming self-aware about the underlying causes of our anger.

Most of these recommendations are self-explanatory, but self-awareness is a little more involved. A starting point could be asking yourself four questions:

Am I angry because I perceive a threat, because I’m not getting what I want, or because of some other emotion (such as sadness or shame)?

If it’s a threat, how does getting angry help me protect myself? Although Seneca would disagree, one could argue that there are situations when expressing anger does help. However, most of the time, it clearly does not.

If it’s because I’m not getting what we want, how does getting angry help me? Even if throwing a tantrum might work in the short term, it’s not a sound long-term strategy.

If it’s because of some underlying emotion, how can I process that feeling in a healthier way?

While there may not be a clear-cut answer to any of these questions, the very act of curiously examining your feelings and sensations can help to calm your limbic system and re-engage the rational parts of your brain. This is a healthier, more effective approach to challenges, and it also increases your psychological resistance to outside influence.

Productive action

One of the benefits of mitigating our own propensity for outrage is that it frees up energy for genuinely productive action. We can shift our attention away from online rage-bait and toward things we can actually control. That could be social – like getting involved in local politics or volunteering in some way – or personal, like choosing to take a walk outside or chatting with a friend. Either way, doing something positive allows us to exercise control, short-circuiting the helpless feelings that drive outrage.

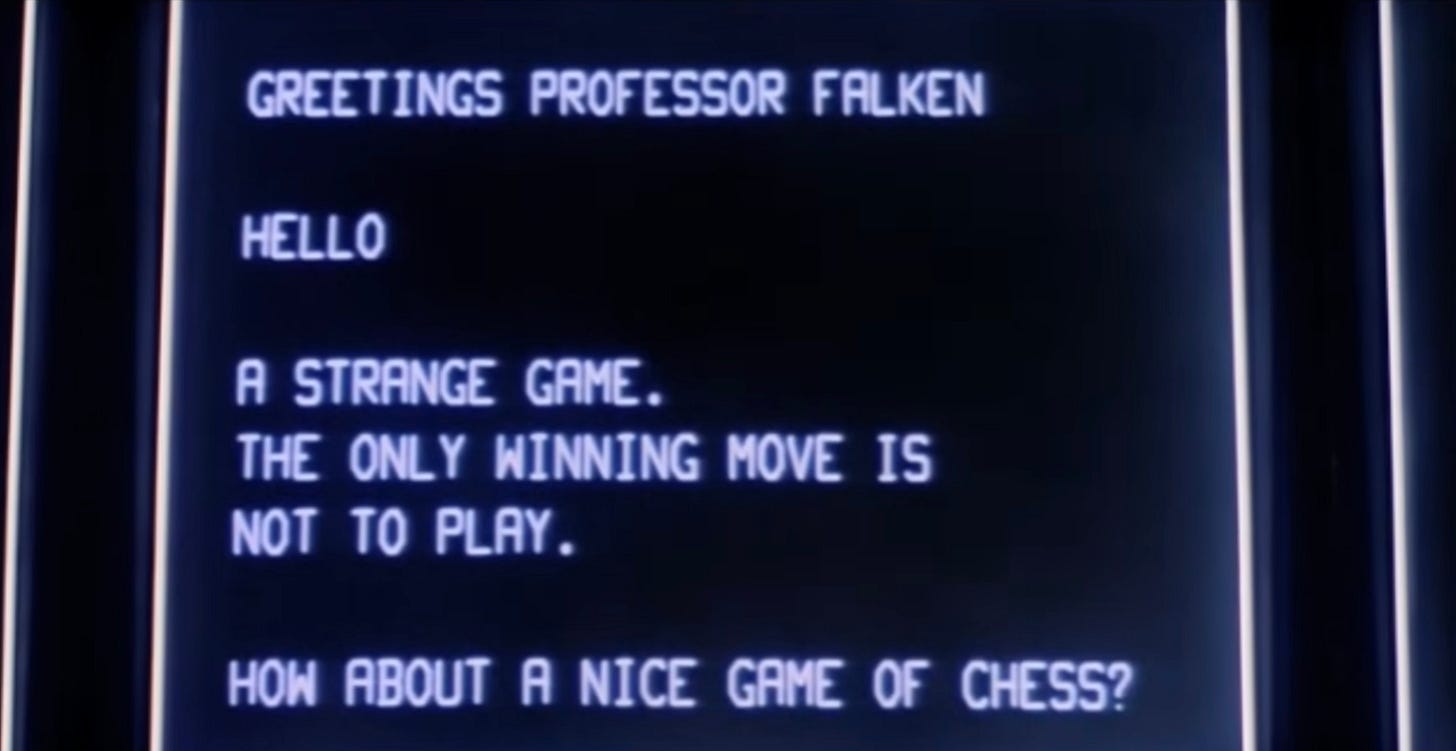

In an environment saturated with provocative content, one of the most effective ways to avoid the brief madness of outrage is simply to turn away. When it comes to the addictive game of anger, the classic ’80s movie War Games had the right idea: the only way to win is not to play.

And thank you for that classic movie reference! I remember watching that with my brother in the theater.

This is so helpful and clearly articulated. Thank you for bringing the philosophers of old to my inbox in such an accessible way.